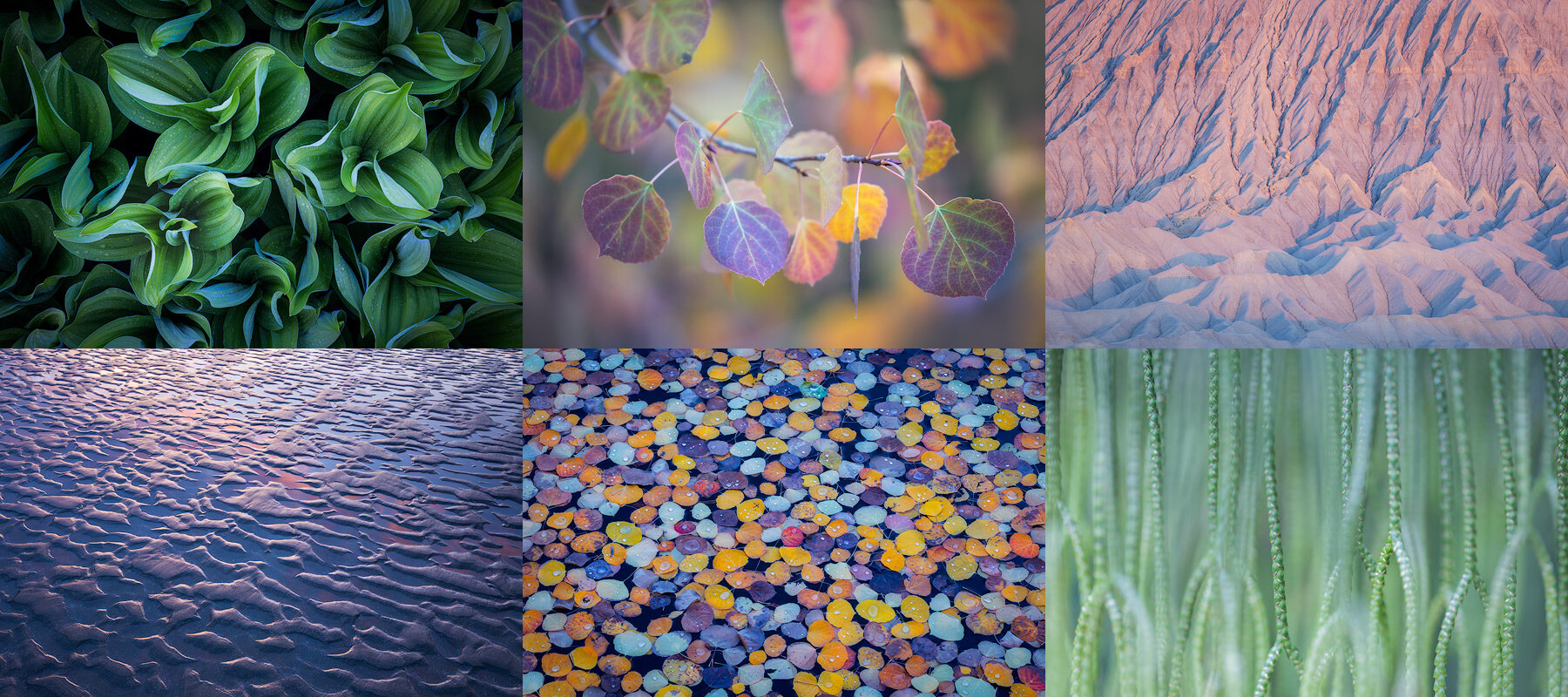

With composition, we are able to take the elements of nature that we connect with the most and arrange them in a manner that communicates our visual preferences and the stories we want to tell about our subjects. In this way, composition serves as an intensely personal window into how we see the natural world and choose to present it through our photography. In writing my most recent ebook, 11 Composition Lessons for Photographing Nature’s Small Scenes, I spent a lot of time thinking about the themes in my composition habits and find that these five ideas are most essential:

#1: Abstraction: See Beyond the Literal Qualities of Your Subject

#2: Simplification: Compose Around a Core Concept

#3: Exclusion: Elevate Your Subject by Eliminating Context

#4: Structure: Seek Out Scaffolding for Your Composition

#5: Details: Pay Attention to the Small Stuff

These ideas are the versatile, practical composition concepts that I return to again and again. Instead of relying on rigid rules (like the rule of thirds) that do not necessarily align with every photographer’s goals for personal expression or every scene we will come across, these ideas are instead tools for the toolbox that we can apply in a wide variety of scenarios to a broad range of subjects.

If you find this article helpful in expanding your learning about composition, you might enjoy 11 Composition Lessons, which includes a 131-page PDF ebook, 6 video case studies, and a PDF field guide for your phone. All of these resources are full of examples and many more specific concepts that you can immediately apply in your own work. I created 11 Composition Lessons to be the educational resource I wish I had years ago, so I hope it can help other photographers accelerate their learning and reach new insights about one of the more challenging aspects of nature photography.

#1: Abstraction: See Beyond the Literal Qualities of Your Subject

Of all the lessons I have learned and now teach about composition for nature photographers, I find this lesson to be the most important. Many people, including me, have come to nature photography without much of a background in art or visual design. This means that we start off with photographing what we see in front of us: mountains, trees, lakes, rivers, sand dunes, and other natural features.

A connection to these literal subjects is often what encourages us to take up nature photography in the first place, so this seems like a logical point to start when creating a composition. However, if we only focus on literal subjects, we leave some of the most important composition ideas and tools untouched. Learning to see beyond these literal subjects to also see abstractions and elements of visual design can help elevate a photographer’s ability to arrange a scene into a cohesive photograph. We can take three examples from this article to show how seeing the abstract qualities of a scene can be helpful for composition:

Seagrass (example #1): The literal subject is seagrass floating in a tidal pool in Olympic National Park. When looking beyond the seagrass as the subject, we can see flowing lines, repetition, and texture.

Mud tiles (example #2): The literal subject is mud tiles found in the Mojave Desert, smooth from a recent rain. If we look beyond the mud tiles, we again see repetition but in a different form than the seagrass. With the mud tiles, we see a network of interconnected lines and repeating organic shapes, all of similar size and scale.

Mossy trees (example #4): The literal subject is moss-covered trees in Oregon. Beyond the trees, we can see mirrored forms (the trees on each side of the middle gracefully curving toward the closest edge), light that adds depth and dimension, repetition, and vertical lines.

All of these abstract qualities are elements we can use to organize a cohesive, visually interesting composition. Next time you are out in nature working on a composition, look beyond your literal subject and think about how you can use lines, shapes, light, and other abstractions to arrange your scene.

#2: Simplification: Compose Around a Core Concept

One of the things I love most about being in nature is the feeling of being overwhelmed with a sense of awe and curiosity. With this feeling, there is so much to take in, from the grandest forms of a landscape to the smallest details. Among photographers, the intensity of the experience of being in an impressive place can lead to the tendency to include as much as possible in a composition – a way to connect the immensity of an experience with the resulting photograph.

When photographing nature’s small scenes, I need to push aside this tendency to want to include too much. Instead, I start by accepting that it is impossible to convey the immensity and complexity of any landscape in a single photo and instead seek to simplify what I see in front of me. After I have decided to make a photograph of a subject, I try to narrow my idea down to one to two core concepts and then let those core concepts drive the composition.

Take the example of the mud tiles above, where the tiles expanded in all directions around me but abruptly changed in terms of shape and texture every few feet, with creosote bushes and other plants popping up between the tiles in random fashion. While a wider view could have shared a more comprehensive story about this desert scene, it would have also been visually disjointed and messy. To simplify, I chose a composition that communicated one concept: smooth, organic shapes connected by a network of similar lines.

#3: Exclusion: Elevate Your Subject by Eliminating Context

One way to simplify a composition is to think about what to include AND exclude within the four borders of your photographic frame. With small scenes, I often think about wanting my subject to feel like it extends in all directions beyond each edge. This typically means that I have made the choice to exclude elements of a scene that add additional context but also hold the power to dilute the overall message of the photograph. Excluding context can help elevate the main subject or core concept as the most important focus of the photograph by removing competing ideas and elements. In terms of composition, exclusion typically means getting physically closer to a subject or choosing tighter framing.

In the sand dune photo above, it feels as if the pastel waves continue in all directions without interruption - the feeling I wanted to convey through my compositional choices. In reality, distractions abound right outside each edge of the frame - creosote bushes, mesquite trees, patches of dried mud in between the layers of dunes, and intermittent footprints. In choosing this framing, I was careful to exclude (or plan to clone out later) all of those distracting elements in order to elevate the subject - repeating waves of uninterrupted sand - as the core concept for the photo. You can see this same sort of exclusion at work in nearly all my photographs of nature’s small scenes. Exclusion helps simplify a composition to allow the viewer’s attention to fall toward the primary subject without competition from less interesting or distracting elements.

#4: Structure: Seek Out Scaffolding for Your Composition

For nature photographers, composition is fundamentally about organizing chaos into a cohesive scene. For small scenes, structure is a key way to organize chaos into cohesion. Structure can take on many different forms depending on the scene. In the simplest terms, I think of structure as the organizing principle behind the composition, or how I arrange the dominant forms of a scene to promote order. Here are three examples of how I used structure to organize a composition for the photos included with this article:

Mossy trees (example #4): Here, the repeating tree limbs are the main structure of the composition, with the limbs on the edges mirroring one another from the center. The limbs are visually dominant and repeat throughout the frame.

Spiral aloe (example #5): If you look closely at the aloe photo below, you will see five sets of leaves that spiral out from the center. Deciding how to arrange these five sets of leaves was the most important composition decision for the scene because they create the main structure for the photo. I chose to center the plant and have the five sets of leaves radiate outward toward the edges.

Mud tiles (example #2): For the mud tiles, the structure of the composition is based on the network of similar repeating lines that bring the scene together.

To explore the concept of structure, think about making a drawing of your scene. If you were to sketch your composition, what would be the first lines or shapes that you would draw? These forms are likely the main structure of your scene. Once you can see the main structure, you can assess other composition qualities like balance and how well the overall arrangement works.

#5: Details: Pay Attention to the Small Stuff

When photographing nature’s small scenes, details matter. With small subjects, details can easily become visual distractions and command attention in sometimes unwanted ways. For example, when photographing a grand landscape, one or two plants with imperfections will fade into the larger scene. When photographing small scenes, those same imperfections can draw a lot of attention and reduce the overall impact of a photograph.

We can consider the spiral aloe above to discuss how paying attention to details can elevate the final result. Think if the crevices of the plant were filled with debris or the individual aloe leaves were covered in splotches of dirt. Such messiness could attract attention away from the repetition and spiral pattern that is the core message of this photo. Think if a cobweb was growing among the leaves or if some of the yellow tips were broken off. Consider the visual impact if the points entered and exited the frame in inconsistent or unbalanced ways. Or, what if bits of the background mulch behind the plant showed up along the edges or in one or two corners? Would the visual impact of these things be positive or negative? My answer is simple: all would be negative visual distractions.

All of these things are small details that might seem inconsequential at first glance or in isolation. But, with small scenes, paying attention to these details and addressing them while in the field is essential to elevating your composition and presentation of your chosen subject. I often find that slightly re-arranging my scene, doing some minor non-destructive clean-up (like brushing off specks of dust with a soft brush), or zooming in a bit can eliminate many distractions and thus help me create a more cohesive and visually compelling composition of a small subject.

Extend Your Learning With 11 Composition Lessons Ebook + Video Case Studies

If you are looking to accelerate your learning and improve your composition skills, you might enjoy 11 Composition Lessons for Photographing Nature’s Small Scenes. This ebook takes a practical approach to teaching versatile composition and design concepts—tools for your toolbox that you can apply in a wide variety of scenarios to a broad range of subjects. 11 Composition Lessons includes a 131-page PDF ebook with more than 160 example photographs, video case studies to help bring the lessons to life, and a PDF field guide for your phone.

“Sarah Marino’s “11 Composition Lessons for Photographing Nature’s Small Scenes” is a fantastic resource for new and experienced photographers alike. She uses her expertise in photographing small scenes to distill a complex topic into clear, logical concepts, each supported by dozens of example images. Several real case studies are also provided to cohesively tie everything together. I can’t recommend this ebook enough!”