This is part one of this series (black and white photos). You can find part two here (portraits of plants) and part three here (color nature photos).

The end of 2024 turned out to be a bit of a whirlwind for me. After we returned from our final destination for fall colors, Zion National Park, I turned my attention to a full refresh of my website galleries. Because I was recovering from a badly sprained ankle, I had a lot of downtime to fill with the tedious tasks of deciding which photos to include, minor reprocessing, keywording, titling, captioning, sharpening, uploading, and then finally organizing. I had planned to get my yearly review posts out before the end of the year but instead shifted all my attention to getting the website refresh in a good place before we headed out to visit family for the Christmas holiday.

After Christmas, we planned to head to Death Valley for a hiking vacation. Almost all hiking in Death Valley is cross-country exploration and I decided a few days before the trip that my ankle wasn’t ready for that kind of terrain. We instead decided on a very last-minute trip to California where we enjoyed some time along the central coast, in Yosemite National Park, and then photographing migrating birds along the Pacific Flyway. Now that I am back home, I have finally had some time to reflect on my photography for 2024 and will be sharing three photo collections: black and white nature photography, portraits of plants, and color nature photography. In each post, I’ll share a few reflections on the year, along with a small collection of my favorite photographs.

After some professional disappointments and failings during the COVID years, I went into 2024 feeling like I needed to devote more effort to personal improvement, especially in terms of being more focused, disciplined, and consistent. While this is all still a work in progress, I ended the year in a better place compared to where I started. One major tangible example of this progress is actually finishing my photos, not just letting the unprocessed photos linger on hard drives. I did a much better job of promptly editing and processing my photos during 2024. In 2025, I need to be better about sharing all those photos.

With regard to working in black and white, I am feeling as excited as ever about this form of creative expression. As part of my website refresh, I looked at many of my older photos in Photoshop and it was shocking to see how convoluted my processing workflow used to be. While I am still somewhat satisfied with the aesthetic result for many of these photos, the path I took to get there was unnecessarily complex. As I processed the photos in this post, it felt good to realize that I can often get to better results with simple Lightroom processing and a few targeted layers in Photoshop for nearly every photo. This simpler workflow makes processing feel like less of a chore so I am more likely to do it and actually enjoy the process.

Onto the photos…

We were fortunate to spend a significant amount of time in and around Death Valley National Park over the 2023-2024 winter and it was such a special time. Hurricane Hilary (August 2023) and then a major atmospheric river storm (February 2024) brought significant rainfall to the park. On the unfortunate side, these storms caused massive damage, closing roads and destroying infrastructure that the park is still working to repair. On the positive side, all that moisture filled Badwater Basin and the surrounding lower elevation areas with the ephemeral Lake Manly.

The fringes of the lake, where the salt and the water merged, evolved over the winter with wind, evaporation, and rainfall, creating dynamic photographic opportunities that lasted for months. The little salt islands that emerged from the standing water, like those shown above, were one of my favorite photography subjects during this time. In addition to Lake Manly, all the rainfall spurred on an unusually long and varied wildflower season. The blooming rock nettle plant at the top of this page was among my favorite finds during our winter wandering.

Lake Manly formed over the Badwater Basin and Middle Basin salt flats. With all this salty water, a diverse range of tiny structures and shapes emerged as the lake evaporated and shifted. While walking around the flooded Devil’s Golf Course area, I came across these tiny interwoven salt cubes under a thin layer of water. I was sick on the day I walked out there and did not have the energy to fully explore this subject since I knew that I still had to walk a few miles back to my car. After I started feeling better, I returned to this spot but high winds had dramatically shifted the lake to the north, obliterating these delicate formations in the process.

After years of photographing Death Valley, one of the things I have come to love most is this dynamic nature of the landscape. That dynamism comes with an important lesson: Photograph your subject while you can because it might be gone when you return. Another lesson: Do not walk around flooded playas like this in the dark. About ten feet from this location, I almost stumbled into a deep hole of water—deep and dark enough that I couldn’t see the bottom.

This is another photo from our time in Death Valley, showing a reflection of the southern end of the Panamint Mountains on a stormy day. While this might look like Lake Manly at first glance, the lake did not stretch this far. Instead, this is a spring-fed pool surrounded by beautiful desert vegetation including pickleweed, sedges, and saltgrass. I decided to take the long route to Pahrump to buy groceries because I wanted to photograph these plants one morning.

When I arrived, a strong wind rippled the surface of this shallow pond so I did not even consider it as a photo subject even though the sunrise that morning was brilliant. After working with the plants for awhile, I stood up to stretch and realized that the lake was calm and the light highlighting the mountains was brilliant, so I made a very quick change of plans. Another lesson: Adaptability, staying aware of your surroundings, and being able to move quickly in response to changing conditions are all essential skills for landscape photographers.

Our fall plans changed at the last minute due to devastating wildfires in Jasper National Park, where we had planned to join up with Anna Morgan for a backcountry hiking trip. Instead, we needed to choose an alternative location that would work for Anna and where last minute RV camping spots would be available for us. With encouragement from Brent Clark, we selected the Upper Midwest.

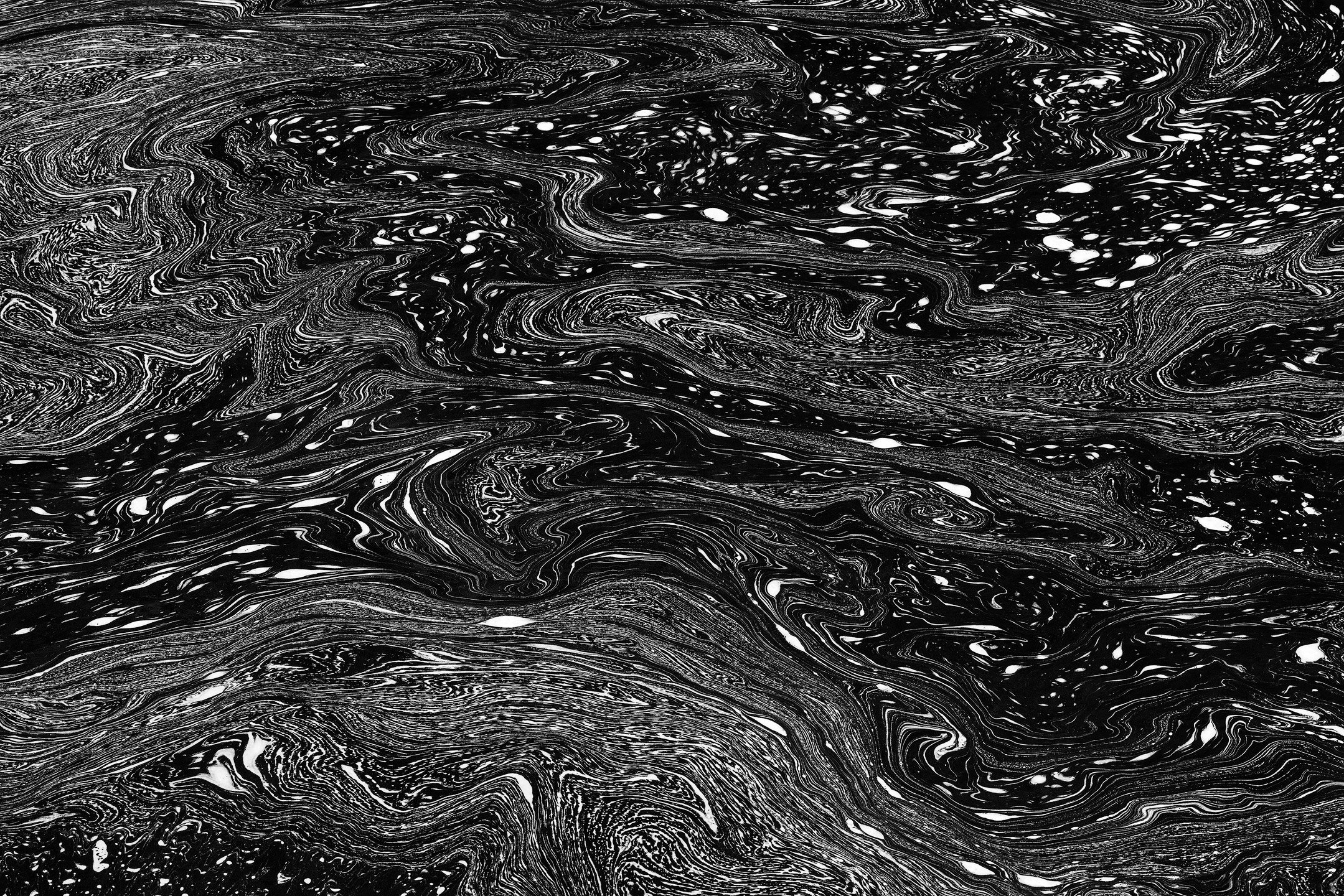

Although the fall colors were very late, Ron, Anna, and I were all quite happy with the photographic opportunities we found, including this writhing expanse of foam in the Porcupine Mountains of Michigan. Standing on a rock ledge above it, we all continually remarked in joyful language to one another that, although odd, this was an incredible find. Whenever I hear photographers complaining about not having anything to photograph, I think of moments like this. If you are open and receptive, the natural world will consistently present you with opportunity.

Our spring travels revolved around seeing the 2024 total solar eclipse in Oklahoma. Since I already wrote a long post about the trip, including our time photographing plants at the Wichita Botanica garden, I’ll keep this section short. Generally, plant photographers seem most excited about perfectly formed flowers. I typically find myself heading in the opposite direction and am instead drawn to the early phases of a plant’s life, including early leaves and new buds. Here, these freshly emerging hosta leaves, in near perfect condition, pulled me in.

The total eclipse! You can read all about it here if you want the full story. Of note in a post focused on reflection, I was so happy to get this photo in 2024 after totally screwing up during the 2017 total eclipse in Wyoming. During the Wyoming eclipse, I did not properly focus my lens and all of my photos were quite soft. I watched that eclipse with a group of photographer friends and my technical failures felt acutely painful as I saw them share their perfectly sharp photos of the corona and diamond ring eclipse phases.

Even though there is nothing creative about this year’s photo, I wanted to create a record of it for myself. With a longer lens, a better understanding of focusing, and a mirrorless camera to help, I was ready when the clouds parted for just enough time to see and experience this awe-inspiring moment.

In June, we returned to Iceland after being away for many years and the most interesting part of the trip for me was experiencing how much I have changed as a photographer in that time. In addition to seeing the landscape in a different way, I was also able to better tune into how much humans have altered the landscape in a way that I did not understand during previous trips. Now, I want to know more about the places I am photographing and reading about the roseroot plant is a simple example of how this knowledge deepened my experience and understanding.

This beautiful native stonecrop used to grow across the Icelandic landscape but, as an appealing food for sheep, it is now relegated to cliffs and other places where the animals cannot reach it. Although I saw a few lovely patches of this plant, nearly all of them were inaccessible (see: growing on steep cliffs). After looking for this plant at every stop, I finally found one as were were ascending some steep stairs to photograph puffins (more on that in my third recap post). The stairs up the cliff helped me finally access one of these beautiful plants, and the wind calmed for just long enough to create a single focus stack sequence.

This is another plant, sea sandwort, that I enjoyed finding in Iceland. It grows along the coast and looks especially beautiful when growing on the South Coast’s ubiquitous black sand beaches. This edible plant, often eaten after fermentation, has shiny green leaves. The silvery shine makes it a perfect candidate for converting to black and white.

I have shared a free ebook featuring my color photos from White Sands National Park and you can read more about my experience in the park in that ebook. For the two photos from White Sands that I am including here, I thought the direct light worked nicely in this higher contrast, darker presentation compared to the softer, brighter color renditions I selected for the same scenes. It seems like many photographers shy away from processing the same file in both color and black and white. I instead enjoy creating these different interpretations, especially since they are often very different and sometimes communicate opposing messages about a landscape or subject.

I probably have about one hundred decent photos of sand ripples at this point so I did not exactly need to add another one to my overall body of work. I decided that this scene, although duplicative of my past work, was worth photographing for two reasons. First, I liked the sense of chaos suggested by the lines, along with the soft gradient from bottom to top. The lines look a little more like an optical illusion than just plain sand ripples. Second, I am increasingly thinking in terms of location-based projects that I work on over an extended period of time.

While I have a lot of photos of sand ripples from Death Valley, I did not have any good ones from White Sands. I want to develop a body of work specific to each place I visit so creating this type of photo makes sense even if I have already worked with similar motifs in other places. After working with a familiar scene like this, I deliberately put effort toward working with new ideas as well, so I am not always just gathering photos of the ideas that come most easily to me.

During our time along the Big Sur coast in December, the area was under a high surf advisory. This meant that many of the rocky beaches were closed for safety reasons. While I had hoped to spend time with some of the wild rocks in this region, that was not possible so I turned my focus to working with the waves. Since this is meant to be a somewhat abstract presentation, I’ll leave my description there.

In 2024, we saw sandhill cranes in Colorado, Wisconsin, and California, along with very rare whooping cranes in Kansas. While I’m still looking for the opportunity to observe them more closely, being able to see them from afar and in flight has felt like a special experience, especially with their distinctive, somewhat haunting calls ringing out across the landscape. Although plain by bird photography standards, I like this photo because it shows off their elegant form in the shape of their wings with their feet trailing behind.

And finally, some ice… I started the year and ended the year experimenting in our yard with ice (more color photos coming soon) during periods of very cold temperatures. After discussing this project with my friend Jennifer Renwick, she shared some tips from her own experimentation with creating ice and I enjoyed some different results compared to what I had been working with earlier in the year. It is addictive to see the patterns form and during the cold spells we have been having this week, I have had to exercise a lot of discipline to stay inside to work on this post instead of making and photographing more ice.

Thank you to everyone who has kindly supported my work in 2024. I’m deeply appreciative of the support! I’ll be back in a few days with more photos from 2024, with a post focusing on my favorite color plant photos.

Sarah Marino is a full-time photographer, nature enthusiast, and writer based in southwestern Colorado. In addition to photographing grand landscapes, Sarah is best known for her photographs of smaller subjects including intimate landscapes, abstract renditions of natural subjects, and creative portraits of plants and trees. Sarah is the author or co-author of a diverse range of educational resources for nature photographers on subjects including composition and visual design, photographing nature’s small scenes, black and white photography, Death Valley National Park, and Yellowstone National Park. Sarah, a co-founder of the Nature First Alliance for Responsible Nature Photography, also seeks to promote the responsible stewardship of natural and wild places through her photography and teaching.